Catherine's house

Catherine's house still sits on 16th Street, a rather forlorn rental now, with its porch enclosed and its gutter hanging—no longer a new and modern home. (Photo by the author.)

Catherine's room

A small room at the top of the stairs in the back of the house on 16th Street is a likely candidate for Catherine's bedroom, perhaps shared with her little brother when her parents hosted a paying boarder. (Photo by the author.)

Catherine's windowseat

One of the few touchingly personal details that come through the newspaper accounts, despite the staggering number of them: Catherine had a favorite place to sit before a bank of windows in her house, thought the exact spot's unclear now. (Photo by the author.)

The Winters attic

Entrance to the attic of the Winters house is through a trapdoor in the ceiling of the largest bedroom, likely the parents'. Catherine's doll stayed there all the years after she disappeared, with the girls' doll buggy, missing-person posters and other memorabilia of the search. (Photo by the author.)

The Winters basement

Once accessed by a trapdoor in the open porch, the basement offered the Winters case its only physical evidence: a much-disputed red sweater, a blue hair ribbon, and a bloody man's undershirt. (Photo by the author.)

16th Street

New Castle's 16th Street was a neighborhood of new homes and middle-class families in 1913. Catherine Winters walked up this sidewalk on March 20 and into infamy—and then into nothing. (Photo by the author.)

Catherine's neighborhood

Catherine ghost stories abound in New Castle. This house a few doors down from hers was in recent years the subject of a Chicago ghost-hunting team, following up rumors of supernatural sightings and bones in the basement. (Photo by the author.)

Dr. Winters' office

A bank (far right) has expanded into the site of Dr. Winters' 1913 dentist office. He occupied a set of rooms on the second floor, and Catherine likely passed underneath his bay window on her way into oblivion. (Photo by the author.)

Catherine and the Gypsies

Sleepy Broad Street storefronts sit near the spot where Gypsies stopped to water their horses at a public trough and several people claimed to have seen Catherine watching. (Photo by the author.)

Downtown New Castle

There were many "last" sightings of Catherine on March 20, 1913, differing in location and separated by several hours, crippling the search effort from the start. Near this spot, Dan Monroe—a family friend who was most widely believed—claimed to share a few words with Catherine just before she vanished into thin air. (Photo by the author.)

The railroad station

One of the few remaining rail stations in New Castle bears testament to one of the nagging theories of what happened to Catherine—that she was lured onto one of the myriad trains criss-crossing the city, either by a friend or a foe. (Photo by the author.)

Henry County Courthouse

Henry County's beautiful brick courthouse, surmounting a rise in the flat Indiana farmland, housed local-government offices and police headquarters in 1913. Some of the most momentous decisions of the case—to suspend the Grand Jury, to abort the murder trial of Catherine's parents—played out within its walls. (Photo by the author.)

The courtroom

In these pews, townsfolk gathered to watch the Winters trial end before it could begin. (Photo by the author.)

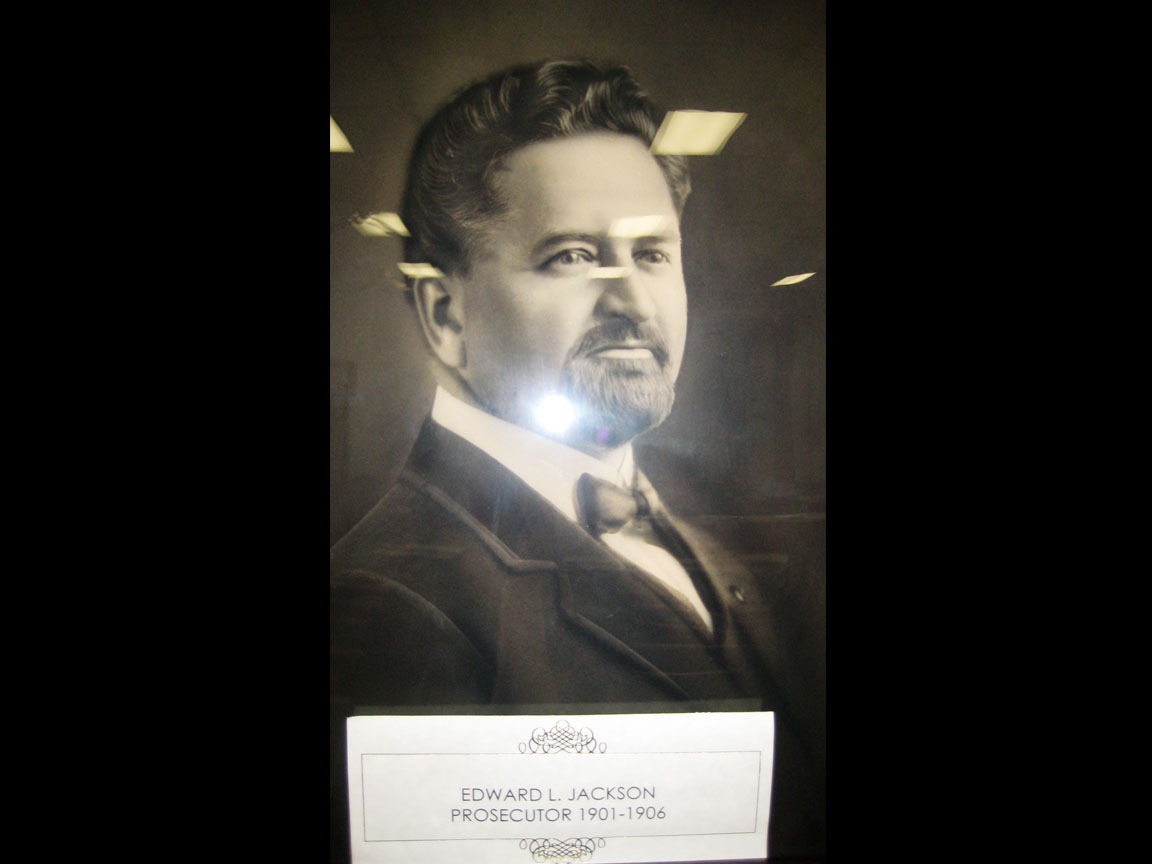

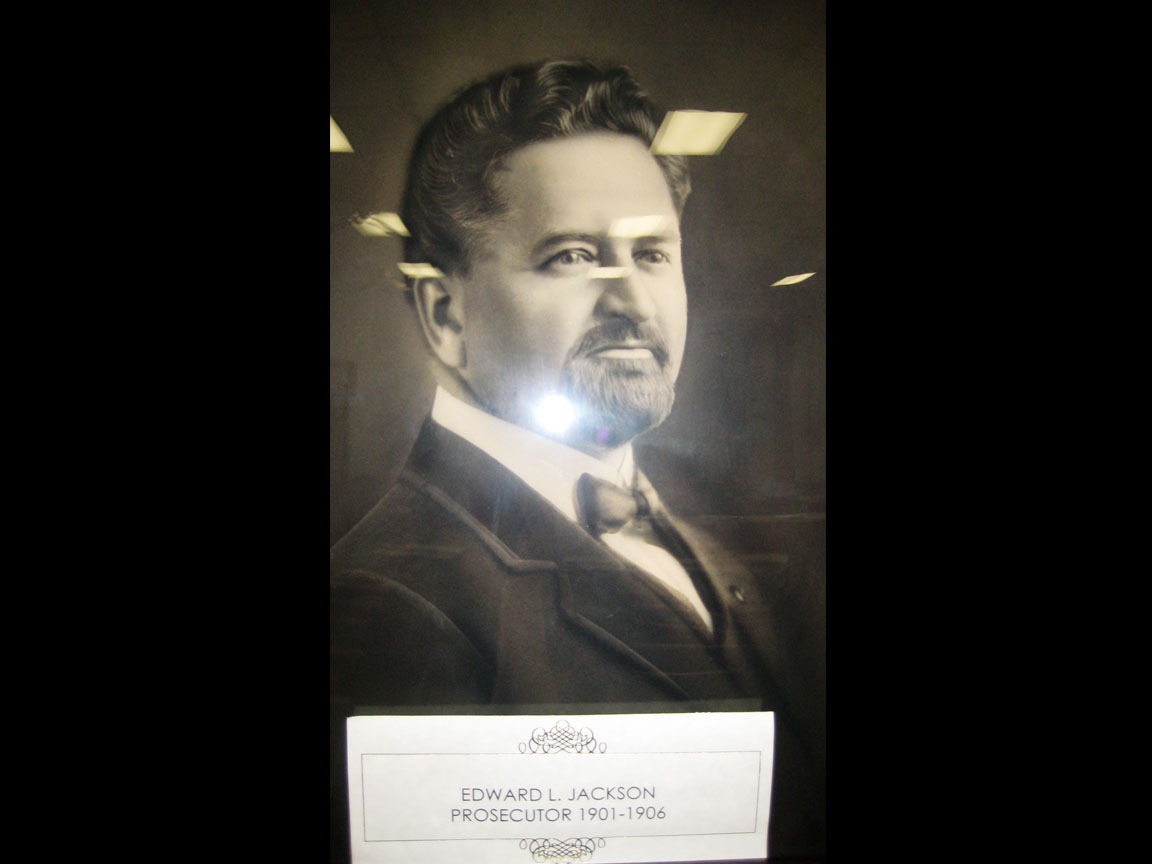

Judge Jackson

Edward Jackson oversaw the Winters grand jury and the aborted trial, and his picture still hangs in the Henry County Courthouse, where he was prosecutor and judge. Not mentioned on its nameplate: his disastrous later stint as Indiana governor, during which he was found to be on the payroll of the KKK and almost universally vilified. He is considered the worst governor in state history. (Photo by the author.)

The courtroom

Eldon Pitts, an East Central Indiana journalist and long-time Catherine Winters researcher, stands in the Henry County Courthouse, where a drop ceiling obscures a gallery and tall windows overlooking the streets Catherine walked on her last day. (Photo by the author.)

Inside the courthouse

Dr. and Mrs. Winters climbed these steps in spring 1914 to be tried for the murder of their daughter/stepdaughter, but left shortly after free citizens when the county prosecutor stunned the town and dropped all charges. Gossip, however, would never leave the Winterses in peace. (Photo by the author.)

The Winters gravesite

Dr. Winters and his second wife are buried in a country cemetery near Mooreland. Half a century later, when the citizens of New Castle raised money for a memorial for Catherine, they chose to place it in the city cemetery, far away from her father and stepmother. (Photo by the author.)

Catherine's memorial

Several New Castle institutions pooled their resources in 2004 to erect a long-overdue memorial for the city's lost little girl. The stone in South Mound Cemetery would, ironically, go missing soon after when the cemetery moved it.

Catherine's memorial

New Castle officials, family descendants, local historians and many others gathered for the laying of Catherine's memorial stone in South Mound Cemetery in 2004. As befit the Catherine Winters story, however, the place chosen for the memorial soon became a source of controversy and cemetery management moved it—without notifying those who had organized the effort, leading them to believe it had, like its owner, disappeared.